Colonel Vincent was on the Taneytown road in the rear of Round Top, awaiting orders near the home of John Weikert, when a messenger sped up from Sykes looking for Brigadier General James Barnes, who commanded the division of the Fifth Corps that included Vincent's brigade. Barnes was hard to find that day and, according to Private Oliver Wilcox Norton, Vincent's bugler and flag-bearer, had not been seen since morning, was not at the head of the column, and "if he gave an order during the battle to any brigade commander I fail to find a record of it in any account I have read."

According to Norton, as Syke's aide approached Vincent and Norton, Vincent, "with eyes ablaze," trotted forward to meet him and called out:

"Captain, what are your orders?"

The Captain replied, "Where is General Barnes?"

Vincent said, "What are your orders? Give me your orders."

"General Sykes told me to direct General Barnes to send one of his brigades to occupy that hill yonder," shouted the captain.

Vincent said, "I will take the responsibility of taking my brigade there."

With that promise Vincent rode back to the brigade. He asked Colonel James C. Rice of the Forty-fourth New York to lead the brigade to the hill as rapidly as possible. Then, trailed by Norton and the brigade flag, a white pennant bordered in red and bearing a blue maltese cross, Vincent galloped off toward the threatened hill. Near Hanover, on the evening of July 1, as he watched the flag of his beloved 83rd Pennsylvania unfurled at headquarters after the long march, he took off his hat and said prophetically to a staff officer, "What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania fighting for that flag."

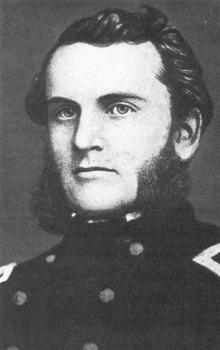

Colonel Strong Vincent's name reflected the man. He was just twenty-six years old, of medium stature, and "well formed." Although quiet and considerate of others and of a cheerful disposition - a gentleman by nature - Vincent was a strict disciplinarian. Beyond that he was a fine horseman, which in that day was an asset for a military man. His young wife, also skilled equestrienne, had visited him on the Rappahannock and their long horseback rides, their gaiety, and their striking good looks made them familiar figures to the army, greatly admired for their ideal love. He had learned the iron molder's trade at his father's foundry in Erie, Pennsylvania, but had not found it to his liking and left it to attend Trinity College and Harvard. He graduated from Harvard in 1859 and read law in Erie until the outbreak of the war.

When war came, Vincent, who had no military experience, became the adjutant of a three-month regiment, an assignment for which reading law might have conditioned him. When the three months were over and that experience was under his sword belt, Vincent became the lieutenant colonel of the newly organized Eighty-third Pennsylvania Regiment that was recruited from counties in the northwestern corner of the state.

The Eighty-third joined the Third Brigade, First Division, Fifth Corps, on the Peninsula and served with that brigade through Gettysburg and afterward. Vincent took charge of the Eighty-third after its colonel had fallen at Gaines's Mill and received formal command of it after Chancellorsville to "the cheers that broke through the solemn decorum of dress parade." It was his privilege to lead it to his native state. Vincent was warmly admired by most other officers because he had made his regiment so precise and splendid in drill that McClellan had rated it first in Porter's division.

Vincent himself hurried to right end of the line, and throwing himself into the breach he rallied his men. It was a hot spot, and Vincent fell with a mortal wound. He died for the old flag on Pennsylvania soil five days later. His last words were typical: "Don't yield an inch." That night Meade sent a telegram to President Lincoln, who issued his brigadier general's commission, dated from the field. President Charles W. Eliot of Harvard recalled Vincent's student days: "He was one of the manliest and most attractive persons that I ever saw." Longstreet later acknowledged him as the man who saved Little Round Top and the Federal army.

|